The Royal Nativity Scene of the Bourbon

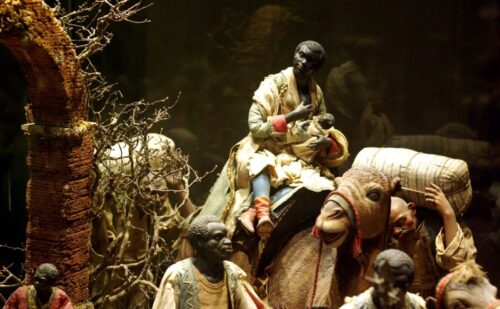

This nativity scene demonstrates how cosmopolitan the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was.

Description

This room, painted in white and without decorations, was intended for the amusements of the court. Today it houses the Bourbon nativity scene, recently restored after most of the shepherds were stolen. The Neapolitan crib tradition established itself with Charles of Bourbon in the mid-18th century, but above all with the collector King Francesco I. It is said that Queen Maria Cristina of Savoy, now beatified, even wanted a small one to keep in her room.

The custom of setting up the crib for Christmas in the Royal Palace of Caserta became a tradition of the entire Court: it was created not only by artists and craftsmen, but also by all the ladies of the court and princesses, very skilled in making clothes for shepherds, rich ladies or Georgian merchants dressed in oriental style, with multicolored San Leucio silks and filigree or coral jewels.

Artists such as Bottiglieri, Sanmartino (the author of the famous Veiled Christ of the Sansevero Chapel), Mosca, Celebrano, Vassallo, Gori participated in the realization, who modeled the most important figures in terracotta, while the others only had the head and limbs of terracotta and the structure of iron wire and tow. The figures were placed on a cork “rock”, according to strict rules and respecting the canonical scenes, such as the Nativity, the Announcement to the Shepherds and the Tavern.

To create the nativity scene, a project was carried out every year, as described in the paintings by Salvatore Fergola visible on the walls of the room. They depict the last nativity scene set up by the sovereigns, before the conquest of the Kingdom in 1860. The last nativity scene was set up in 1845, on the occasion of the inauguration of the Naples-Caserta railway. Maria Sofia, the last Queen of the Kingdom, was setting up the nativity scene in 1860, but she didn’t make it in time due to the attack by the Savoys and the subsequent fall of the Kingdom.

The current set-up is inspired by that last 19th-century nativity scene, which well represents the cosmopolitan Naples of the end of the 18th century.

When the Bourbons set up the Crib

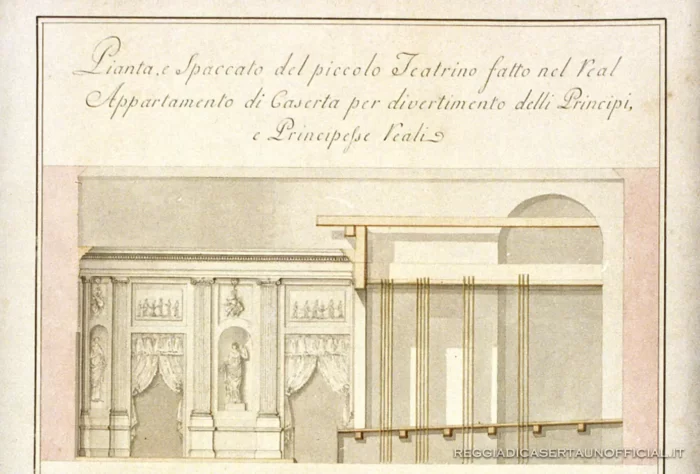

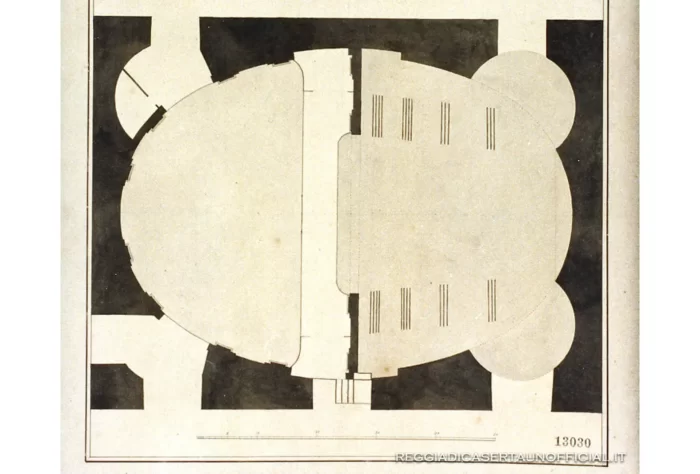

“When the traditional date of December 12 was just a few days away, the activities in the palace of Caserta became frenetic: the royal nativity scene was set up, one of the great passions of King Ferdinand. With muffled “jamme…jamme!” and anxious “E stateve accuorte!”, the director of the crib incited and supervised the continuous coming and going of the employees who brought hundreds of shepherds, with rush baskets and protected by “reeds”, from their distant cabinets up to the large oval hall, in the center of the eastern side of the building, often also a domestic theatre. There, the cribs, under the guidance of scenographers and painters, positioned them: the most beautiful and most precious shepherds were placed in the foreground, then there were those in the background and finally those, smaller and more ordinary, ‘for the distances ‘.

Finally the day of the inauguration arrived: King Ferdinand and Queen Carolina, followed by the court, entered the room almost in the dark. Then, while a soft music spread from above, slowly it began to get light as at dawn, thanks to a device that imitated the hours of the day invented by the architect Nauclerio, until, in full light, the crib appeared in all its jaw-dropping beauty amidst a chorus of exclamations of delight and surprise. Immediately the eyes wandered greedy and fast on the many characters and animals that crowded the scenography, but the curiosity of most was, above all, in recognizing which members of the court had been portrayed among the shepherds and, as they were identified, it was all an indication , smile, wink and whisper comments, especially when, as often happened, those recognized were powerful and proud personalities such as the Marquis Tanucci with his wife. Even Ferdinando and Carolina had a lot of fun, perhaps not by chance, with those satirical reproductions of their courtiers and, when once the King discovered that even his beloved greyhounds had been faithfully reproduced by the good crib maker Vassallo, seized by irrepressible enthusiasm, he he got tired of pointing them out to the guests with colorful dialectal expressions….”

Taken from: Nando Astarita – “Caserta dei Borbone”

The nativity scene becomes fashionable

This sophisticated royal pastime was soon imitated by the nobles and rich bourgeois who, from the best artists, asked for nativity scenes that were as much a symbol of their wealth and power as possible. Thus, a nativity scene had large silver roses all around it to place the candles and in another, belonging to the prince of Ischitella, the Magi had clothes that sparkled with jewels and the donkeys following them filled with precious stones. The frenzy became such that some even went into debt or ended up in poverty just to have the honor of the king visiting their crib. In fact it had become fashionable, on Christmas days, for the King and the Court, and sometimes also other sovereigns and illustrious foreign visitors, such as Goethe, to admire the most renowned ones and in the most exclusive houses, which were then also opened to the people who remained amazed.

The result of all this was an outpouring of this passion: there was no family, however humble, that did not have its own ‘presebbio’, even if it was tiny and, if there was no space, it was placed in the “cabinet”, a case of wood hanging on the wall. Meanwhile, the crib scenography had become increasingly theatrical and less and less religious. Palestine had been transformed into the Neapolitan alley animated by every kind of craftsman and the tavern with its “hanging”. So that, in all that typical “ammuina” of peasants, tacky with gozzo, spaghetti eaters, beggars, water carriers, pisciavinnol’, verdummari, Magi with a large following and all surrounded by many animals including even buffaloes, only thanks to the swarm of angels who descended from heaven it was possible to identify the Nativity in some ravine of the immense “rock”. In short, this “courteous” nativity scene no longer had any of the mysticism and sacredness of the Franciscan one and, rightly, the great collector Cuciniello defined it: “a page of the Gospels translated into Neapolitan dialect”. In fact, what was represented was a cross-section of Neapolitan life rich in a thousand religious and pagan symbolisms, a neo-realistic show that was always up-to-date, not only in the costumes, but also with the novelties of the time, such as the ruins of Greek-Roman temples, after the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum wanted by Charles III, or as the faithful reproduction of the first elephant that arrived in the capital on the occasion of the embassy of the Ottoman Gate to the Kingdom of Naples.

Taken from: Nando Astarita – “Caserta dei Borbone”

The nativity scene becomes a tradition

The tradition of the crib was opportunely encouraged by the Bourbons, certainly not out of religiosity, but because they were well aware of how politically advantageous it was for the people to recognize themselves as the ‘main interpreter’ of a phenomenon loved by the King and the nobility. Then, the revolution of 1799 and the arrival of the French interrupted the tradition of royal cribs and most of the shepherds were lost and stolen, perhaps for the benefit of various museums around the world. But, on their return in 1816, the Bourbons, after having bought hundreds of new shepherds, resumed having the crib set up even if, with the new century, it will begin to lose vitality, so much so that it will remain forever ‘eighteenth-century’. In reality, the most beautiful nativity scene set up in Caserta was that of 1844, with almost all the shepherds of the royal collections and with three processions of Magi, an expedient to give temporal dynamism to the scene and to greatly expand one of the most scenographic groups. It was huge and was therefore exhibited in the ‘Racchetta’ gallery with the ceiling repainted in blue for the occasion, and for its beauty it was portrayed in four canvases by the court painter Fergola and admired, until the usual 2 February, the day of Candelora , by a large crowd that arrived in Caserta also thanks to the recent (1843) railway that connected it with Naples.

Taken from: Nando Astarita – “Caserta dei Borbone”

The manufacturing technique

Taken from: Nando Astarita – “Caserta dei Borbone”

Shepherds underwent an evolution: by now sculpting them had become too slow and expensive for their growing demand and therefore – after passing from the first large painted wooden silhouettes (1025) to life-size polychrome wood sculptures (1200), and then to dressed statues, but increasingly smaller (1500/1600) – they came to use tin molds which allowed a rapid and economic reproducibility of shepherds in clay. Instead, for the most valuable ones, the Neapolitan genius invented mannequins in iron wire covered with tow, to which terracotta heads, hands and feet were applied, so that they could assume different and more realistic positions. Furthermore, the obsessive attention to detail led the artists to specialize: some modeled heads, like the famous Sammartino, founder of a school in San Gregorio Armeno, some hands and feet, some animals and some, like Ardia, known as the “Farinariello” , baskets of fruit and vegetables, while master potters from Vietri and Cerreto modeled tiny jars and plates. In short, it was a real art, that of cribs, not surprisingly already in the fifteenth century called “figuram sculptores”, despite the opinion of Vanvitelli who, privately, defined the crib as “a girl to whom the Neapolitans, clumsy for the rest , they dedicate themselves with effective skill”.

When the hall was the Teatrino Domestico

The elliptical room, now undecorated, was used by the royal family as a domestic theatre. This is also seen in the 1799 inventory where it is indicated as the “Room of the Real Theatre”: there was a place for the Audience, the orchestra with a harpsichord and piano, the stage and the scenery, still intact at the end of the century. Today it houses a monumental Neapolitan nativity scene made up of 1200 figurines.

External Link