The Grand Staircase of Honour of the Palace of Caserta

The Scalone, by Luigi Vanvitelli, is the most spectacular scenography of the 18th century and was imitated all over the world.

Introduction

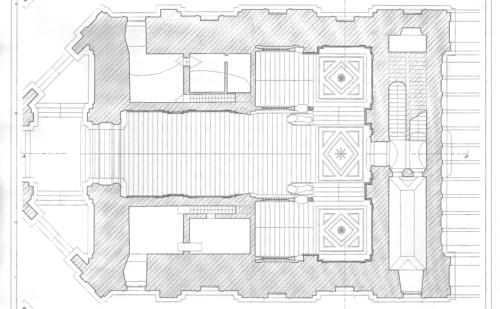

The Grand Staircase is the visiting card of the entire Royal Palace of Caserta, and the place where the grandiose vision of the Vanvitelli. The Scalone and the two vestibules constitute a real jewel of architecture in which the genius of Vanvitelli expresses his utmost creativity. Perfect synthesis of classicism and Baroque theatrical scenography, it forms the fulcrum of the other parts of the Palace.

Vanvitelli, in order not to break the optical effect of the famous Cannocchiale, placed the Scalone in the center of the building on one side of the vestibule. Here stands the Farnese Hercules, which on one side hides from view the entrance to the foyer of the Court Theater, on the other it watches over the entrance to the Scalone d’Onore.

The Grand Staircase at a glance

The Grand Staircase of the Royal Palace of Caserta is such a masterpiece of architecture and scenography that it became the model from which all subsequent great staircases in the world were inspired.

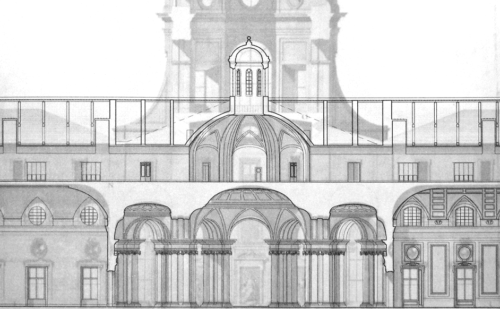

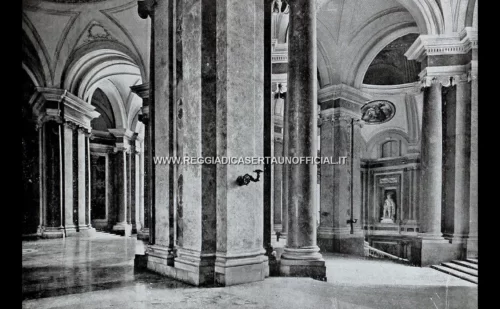

Climbing the first steps, the staircase immediately appears majestic and immersed in a tranquil light, accentuated by the subtle chiaroscuro of the marbles and decorations. Going up the vision becomes more and more complex as you reach the upper gallery with two marble lions on the sides, a symbol of power and majesty, and in front an enormous wall dominated by the immense statues of Merit, Royal Majesty and Truth.

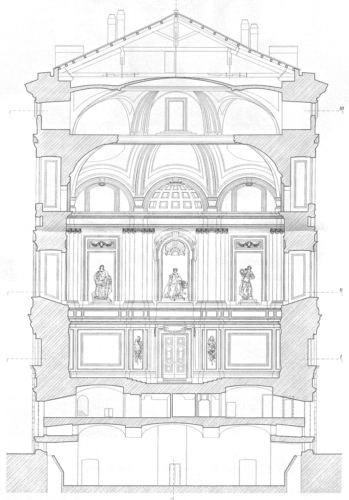

Now, turning around, you will notice that what you thought was the final part of the staircase suddenly expands into two enormous and spectacular parallel staircases ending with a structure of arches and columns recalling the shape of a temple. Only now will you be able to admire all the majesty of the Grand Staircase and notice at the top, at 42m high, an enormous dome that dominates it.

Only now will you be able to admire all the majesty of the 32m high staircase with a volume of 11,664 m3, and which ends at the top with a dome which originally housed an invisible orchestra. This dome is actually “fake”, as above it there is another suspended from the roof by wooden tie rods… an extraordinary masterpiece of imagination.

While climbing up the side staircase you will admire all this, you will reach the large central vestibule, almost a temple, which gives access to the Chapel and the Royal Apartments.

The magnificence of the Grand Staircase, with its marble, the enormous statues, the elegant arches, the two enormous staircases, constitute the most spectacular scenography of the 18th century.

Now from the upper vestibule you will finally be able to access the Antechambers of the Royal Halls, and the Palatine Chapel.

The visual impact is immediate and dazzling for anyone who passes through the telescope for the first time: the short initial staircase limited by two pillars of the vestibule, and dominated by a large arch (having the same inclination as the Grand Staircase) inevitably pushes us to climb.

Great world staircases inspired by that of the Reggia

The Grand Staircase of the Royal Palace, as mentioned earlier, has influenced the structure of the most beautiful staircases of the world. Is easy to find its style (a central staircase splitting into two lateral staircases ending in a large tripartite wall). A simple web search with Google proves it.

The visual impact is immediate and dazzling for anyone who passes through the telescope for the first time: the short initial staircase limited by two pillars of the vestibule, and dominated by a large arch (having the same inclination as the staircase) inevitably pushes us to climb.

Now begins the perceptive game of Vanvitelli . Going up the staircase (steps 8m wide and made of a single piece of Lumachella stone from Trapani), we will notice the marble side walls which, illuminated by the reflection of the invisible upper windows, give light to the staircase and at the same time lead to looking only upwards and never sideways. Following the decorative motif of the side walls, one reaches the upper gallery.

Initially it should have had the same width as the other ramps and also two lateral balustrades, but Vanvitelli decided to widen it and remove the balustrades to increase its monumentality. In fact, the steps are formed by a single 8m wide slab, so that there are no joints to distract our attention.

The lions

The upper rectangular landing is dominated on the sides by two marble lions to signify, as can be seen from the “Declaration of the Drawings” by Vanvitelli, the strength of reason and weapons that ensure the king the “ownership of his kingdoms”. The lion on the right is by Tommaso Solari, while the one on the left is by Paolo Persico.

The first landing

The upper rectangular balcony is dominated on the sides by two marble lions to signify, as can be deduced from the “Declaration of drawings “by Vanvitelli, the strength of reason and weapons that assure the king the “possession of his kingdoms”. The right lion is the work of Tommaso Solari while the one on left is by Paolo Persico. In addition to having a symbolic and decorative function, the lions also have an extremely practical function for Vanvitelli: if they weren’t there, climbing the staircase, one would notice the angle at the junction between the wall and the upper balustrade of the second staircase, canceling the much sought-after surprise effect.

The three statues

At the end of the staircase we find the immense back wall. It is divided into three main sections dominated by three huge sculptures. The three enormous statues were commissioned by Vanvitelli to intimidate visitors during the ascent. They represent Merit, Royal Majesty and Truth.

At the end of the Grand Staircase we find the immense back wall. It is divided into three main sections dominated by three huge sculptures surrounded by frames, and above by three arched elements, two of which have false painted windows, and in the center by a coffered semi-dome. Below the central statue there is a large door flanked by two semi-pillars decorated with bas-relief trophies. Observing the central statue, it is possible to notice behind it the presence of a room from which, through a circular ramp, the musicians climbed to the top of the vault of the Grand Staircase.

This is the only time Vanvitelli allows the gaze to move freely, while usually in the Grand Staircase every single movement of our gaze is not spontaneous, but skilfully calculated by the architect. This does not happen in other large European staircases such as, for example, the one in Palazzo Bianco in Genoa and in the Würzburg Palace, where the decorative abundance and the shape of the ramps disperse our attention.

We could also add that, probably, Vanvitelli inserted the space behind the Maestà Regia to distract us for a moment from continuing the climb, as this further increases the surprise effect by turning around.

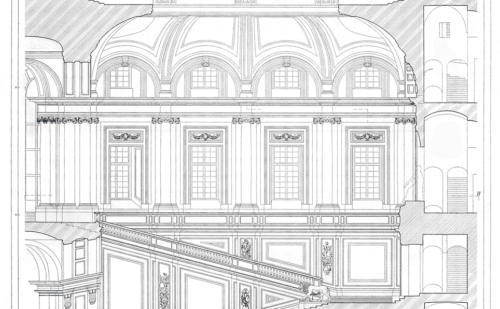

Relief of the facade with the three statues of the Grand Staircase

The three enormous statues were commissioned by Vanvitelli to intimidate visitors during the ascent. Let's read his words extracted from the Declaration of drawings of the Reggia of Caserta (adapted):

Among the many subjects that can be adapted to this project, these three were chosen because they seemed the most suitable. There are two main reasons why subjects usually ask for an audience with the king: one is to ask for protection, the other is to claim positions. But as among those who go to complain sometimes there are also slanderers, such as those who have blatant claims, so to keep them away from the ears of the Prince, from the very beginning of the ladder they are warned not to come here to defame anyone, nor let him come and demand something if he himself has no merit, because the Majesty of the King, just judge of truth and merit, will not let himself be enchanted by them.

Vanvitelli's original project envisaged an inscription under each statue, later not added.

QUI GRAVIS ES MERITO GRAVIOR MERCEDE REDIBIS

(greater is the merit, greater will be the reward)

AD MAJESTATEM ACCEDENS PERPENDE QUID AFFERS

(before approaching the Majesty think on what are you pretending)

Artist: Tommaso Solari

The imposing Royal Majesty, the largest of the three statues, is placed in the most majestic niche of the three to indicate the greater importance of the figure of the King. The statue surmounted by the shell, a classic symbol of Vanvitelli, is equipped with a royal cloak and crown. and she is seated on a lion which, in addition to being the logo of the Spanish royal coat of arms, is a symbol of power and clemency, virtues that belong to the King. To symbolize command, in her right hand she holds a scepter with an eye open to ” denote that he knows what he commands ”, while with the left he stops the lion to mean that the King blocks not only the small subjects but also the great ones.

VERA FERENS VENIAS LATURUS FALSA RECEDAS

(come forward the true, hide the fibs, go away the falsities)

Artist: Gaetano Salomone

The Truth (imagined with one foot on the world and one finger pointing to the sun.

The Truth, represented by a woman dressed in an almost transparent toga, means that, as Vanvitelli himself says, “no matter how much she covers herself, she always shows the beauty of her nakedness”. In her right hand she raises a sun, and as it illuminates the universe, the Truth also illuminates invisible things. He also has the fingers of his left hand bent except the index with which he points to the sun, and his left foot resting on the world to indicate that truth always triumphs.

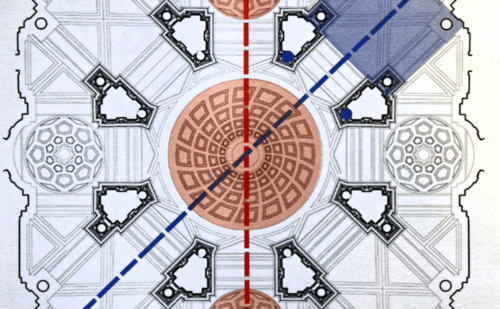

The upper vestibule

Climbing the second ramp, you enter the vestibule, which looks almost like a temple and is structurally similar to that of the ground floor, but much more elegant and rich in ornaments.

It is difficult to establish where the Grand Staircase ends and the upper Vestibule begins, there are no doors or gates that clearly separate the external space (the Cannocchiale) from the interior of the Palace. the upper vestibule can therefore be considered as the last portion of external space before accessing the Royal Apartments or to the Palatine Chapel.

Here they also shot a famous scene from the film Star Wars episode II: attack of the clones

Perfectly octagonal in shape, it is surrounded by a portico, and this evokes late ancient architecture (for example the church of S. Costanza in Rome, the Palatine Chapel in Aachen) and medieval buildings, such as the Byzantine San Vitale in Ravenna, but above all it recalls the Venetian basilica of Santa Maria della Salute by B. Longhena. The octagonal structure made it possible to keep the central part free, and to distribute a category of people (court ladies, dignitaries, prelates, court staff, etc.) on each side of the portico that surrounds it, separating them from the pillars.

As can be seen from the project sketches, Vanvitelli attributed extreme importance to this barycentric space because:

- It is the main passage node of the entire building;

- It is the center of the building from which the two orthogonal arms that divide it branch off;

- It should have supported a large dome with an octagonal base to be able to observe the new city of Caserta under construction from above, but also because it would have become the focal point of the building seen from the very long straight avenue that should have united the Royal Palace to Naples.

The architectural structure of the vestibule

As previously mentioned, the upper vestibule has the same structure as the lower one, but is different in appearance. In fact, if you compare them by observing them from the landing of the central staircase, you notice that the lower one is immersed in semi-darkness, with the mighty columns supporting the weight of the overlying structures. Looking up towards the upper vestibule, framed by a three-arched portico, one notices a brighter space revealed, elegant in the use of the Ionic order and polychrome marble, and with the four twelve-metre-high windows overlooking the four internal courtyards.

The upper vestibule is divided into two different height levels, with the central part raised and connected by seven steps. In addition to having a functional and aesthetic function, this allowed Vanvitelli to reduce the inclination of the lateral ramps of the Scalone d'Onore. Without these seven steps, unless the lateral ramps were inclined, or the height of the Cannocchiale was reduced (and therefore it would also have had to modify the appearance of the external facades), it would also have had to reduce the height and proportion not only of the portico but of the entire upper part of the staircase at the level of the windows and statues. A simple solution that demonstrates Vanvitelli's genius and practical sense.

These seven steps invite you to an inevitable stop: here with a perfect synthesis of Utilitas and Venustas (Utility and Aesthetics, or Form and Function, the basic principle of good design) , you will notice that of the eight sides of the portico that surrounds the central room, four have a recessed circular ceiling, four have a cross vault, and it almost seems that the entire room wraps itself in the spiral of the large central dome. Positioning yourself in the center, you will notice that, on the contrary, it seems that the entire Palace expands from that point. It is in this precise point, in fact, from which it is possible to observe the Royal Majesty, from another side the succession of monumental halls, the Palatine Chapel but also to cast an oblique gaze at the large windows that overlook the four courtyards.

At the center of the Vestibule there are eight large Ionic pillars of trapezoidal shape, equipped with six pilasters (flat columns), two marble columns with a brighter color, useful for making the pillar slimmer and for emphasizing the central room, but also for directing the gaze towards the halls or towards the windows. The succession of columns and pillars that intersect with the arches and vaults creating many perspective vanishing points is nothing more than the materialization of the Baroque theatrical scenography "view with multiple fires" by Bibiena, where the theatrical backdrop, in fact, has a decoration with perspective with multiple vanishing points. This proves not only Vanvitelli's past as a set designer, but demonstrates his creativity and great practical sense.

The dome

The light from the large side windows gathers in the immense vault which in turn reflects it downwards. The vault was painted by Gerolamo Starace and represents “Apollo’s palace”, and has a central oculus, as above it there is a space intended for the orchestra that played when the King climbed the Staircase.

- allowed you to better divide the interior space;

- allowed you to increase the height and thus make it visible from afar until it became a symbol;

- the gap between the two domes made it possible to hide the internal structures that support the domes.

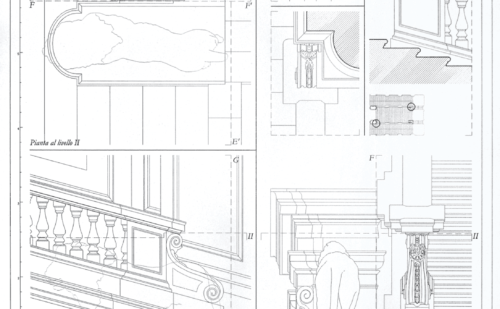

The architectonic structure of the Grand Staircase

The original project in the Declaration of the Drawings of the Royal Palace of Caserta

How did Vanvitelli arrive at this architectural masterpiece? The references of his previous works in the Royal Palace of Caserta are evident, none had ever reached such high levels of imagination, art and construction technique, pictorial sensitivity and perspective virtuosity, audacity and mathematical calculation. But if you look at his sketches for set designs, and think of the pictorial style of his father, the famous landscape painter Gaspar van Wittel, you are no longer surprised: on the one hand, he inherits his father’s style made up of large spaces full of light and subtle variations of colour, and on the other hand, the Scalone d’Onore seems to be the physical realization of one of those architectural backdrops by the Bibienas which marveled the theaters of Europe, but with the fundamental difference that the constructional difficulties overcome by Vanvitelli were very different from those faced from the theatrical set designers, who only had to create a decorative effect and seen from a single point of view (the stalls), Vanvitelli had to create an enormous and real architectural structure, and with as many as six points of view (lower vestibule, staircase, balcony, upper stairways, dome and view from the upper vestibule).

The Grand Staircase of Honor of the Royal Palace of Caserta had a revolutionary effect in world architecture, so much so that today it is very easy to find its style in the countless entrance staircases of the most beautiful palaces and theaters in the world.

Dimensions of the Grand Staircase

(to be understood as minimal)

- 18x24m (lxp excluding window depth)

- Height at first dome level: 27m

- Height at second dome level: 32m

- Height at the level of the structures supporting the dome: 38m

- Width of the stairs: central 8m, lateral 5m each

- Total volume excluding upper vestibule at first dome level: 11.664m3

- Upper vestibule: 27x27m

The columns

The walls of the Grand Staircase are punctuated by minimal protrusions and recesses, elegant decorations and Ionic semi-columns, and are covered with gray and pink marbles skilfully arranged to create a subtle chiaroscuro effect. The Ionic semi-columns have a giant order1, are flanked by pilasters2, and frame the window compartments. For greater precision it must be stated that it is partially incorrect to speak of semi-columns, as they are incorporated into the wall only for 1/4.

Lighter and more delicate than the previous Tuscan order of the lower vestibule, the Ionic one, despite not reaching a particular perfection, has the merit of being almost free from defects, as it is not too massive like the Doric order, nor too refined like the Corinthian.

Following the principles of Vitruvius and Vignola, to remedy the bad ionic base (the heavier elements that compose it are not placed at the bottom, but at the top, and this damages the solidity), Vanvitelli replaces it with the beautiful base attica: two toruses (discs) of different thicknesses connected by a scotland (recess), creating a magnificent effect, as it integrates solidity and beauty.

Instead of the flat Ionic capital he used the modern Ionic capital , which having protruding volutes and the concave abacus, allowed it to stand out from the wall. The ionic entablature is simple and elegant, and divided into three bands of different heights.

The proportions

The analysis of the proportions of the columns of the Grand Staircase of Honor of the Royal Palace of Caserta

The proportions of the individual elements are very close to the Ionic order described by Palladio in which the column is 19 modules high and the entablature 4. In fact, in our case, the column is equal to 19.5 modules and the entablature is always 4.

Vanvitelli did not have any second thoughts about the architectural order to choose: the Ionic order is used both in the drawings of the Declaration and in the execution. The proportions of the column remain roughly the same, what changes significantly is the entablature: in the project it is 2.5 modules high, in reality double that.

In the Scalone d'onore, taken as a whole, the use of the order is completely classic, as excluding the niche from the coffered vault that houses the central statue, there is no trace of details of Baroque derivation.

Vanvitelli, in general, fully confirmed himself as an exponent of neoclassicism, trying to use the classical orders according to the ideal canons. The perfect correspondence in proportions to Vignola and Palladio are proof of this. The architect grants the innovations or variations from the model in the Tuscan style, in search of an otherwise unobtainable impetus, and in the individual parts of the orders, in particular the bases and capitals: the former more rational and effective in giving the idea of valid support to the column, the latter, particularly in the composite, simpler and more elegant, in search of the sobriety that distinguishes his work in Caserta. The architect emerges from the research as a protagonist of his time who ferries the Italian architecture of the eighteenth century from the Baroque to the Neoclassical.

- 1 Giant order: when the height of the column is greater than that of a floor.

- 2 Lesena: semi-pillar protruding from a wall.

Light control

In the Grand Staircase there is an extraordinary lighting control. The windows are placed very high up, and are of two types:- a row of smaller, barrel-shaped upper windows (two are painted, therefore fake) ;

- a second row of rectangular shape and much larger in size.