Capua: what to visit

The new Capua is a city of medieval origins, where the Italian language was born and is the seat of the remarkable Museo Campano

The city of Capua, founded in the 9th century on the site of the ancient Casilinum (the Roman Capua is in fact the current Santa Maria Capua Vetere) and has a historic center of great interest, several Lombard churches and the remarkable Campano Museum, with the vast collection of Matres Matutae, female sculptures that hold infants in swaddling clothes, testimony of the Italic cults of this area, devoted to the cult of the family and fertility.

Capua is also the place where the Italian language was born, since here in 960 the first document in the Italian vernacular was drawn up, the so-called Placito Capuano, celebrated with a plaque in one of the city’s squares.

History

The new Capua was founded in 856 by the Lombard count Landone I to welcome the exiles who escaped the destruction of the ancient city by the Saracens. In fact, in 841. The Capuans took refuge on the Palombara hill near Sicopoli (current Triflisco), but the houses built in wood were set on fire and so in 856 they built the new city on a bend in the Volturno, in the place where the Roman Casilinum had risen in the past. , a small river port that served the ancient Capua. The settlement of Casilinum also played an important strategic function as it stood guarding the bridge over which the Via Appia crossed the Volturno. and resisted for a whole winter to the armies of Hannibal in 216 BC. during the Second Punic War; it then became a colony with Julius Caesar (in 58 BC), to be finally abandoned in the following centuries. Between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Capua was a principality several times, an important stronghold of Naples, capital of the Kingdom. Throughout the Lombard and Swabian period it was the prince center of Terra di Lavoro, then replaced by Caserta in the second Bourbon period. The events of the new Capua were characterized by a succession of sieges and war episodes – testifying to its strategic and political role as a “gateway” to the South – the bloodiest of which was the sacking by the troops of Cesare Borgia, who in 1501 they entered its walls under the pretext of a truce and indulged in atrocious violence. In the following centuries the city was occupied by the Austrians (1707) and reconquered by the Spaniards (1734), then it underwent two occupations by the French, in 1799 and then again in 1806. In 1860, at the end of the Volturno battle fought between the Garibaldi and Bourbon troops, Capua was besieged by the Piedmontese army led by general Marozzo della Rocca. The city fell on November 2, and it was here that the armistice between the Savoy and Bourbon armies was signed.

Attractions of Capua

Basilica of S. Angelo in Formis

Not far from Capua stands the Benedictine basilica of S. Angelo in Formis, founded in the 10th century on the ruins of the temple of Diana Tifatina. It is one of the most important medieval monuments in Campania as it represents the most complete testimony of Cassinese architecture and art after the destruction of the abbey of Montecassino during the Second World War. It contains a cycle of medieval frescoes, inspired by stories from the Old and New Testament, among the largest and most complete in southern Italy in the Byzantine style, it is in fact mentioned in many school texts.

The Campano Museum and Antignano Palace

One of the most important museums in Southern Italy, with unique collections in the world.

The Museum is divided into various departments: Archaeological, Medieval, Renaissance, Art Gallery and an important Library. It occupies 32 exhibition rooms, 20 storage rooms, three large courtyards, a vast garden.

Inaugurated in 1874 and completely renovated in its facilities and fittings in 2010, the museum houses collections of artifacts dating back to antiquity as well as statues and frescoes from sites in the area. In the archaeological section, the collection of about 200 votive statues of Mothers stands out, found in the sanctuary dedicated to the Italic goddess of fertility Matuta, discovered in 1845 in the Fattarelli estate near Santa Maria Capua Vètere.

Antignano Palace

The Campano Museum is housed in the historic Antignano palace whose foundation dates back to the 9th century and incorporates the remains of San Lorenzo ad Crucem, a Lombard age church on the site of one of the three noble seats of the city. The building boasts a splendid Durazzo-Catalan portal.

Discover the Campano Museum

Discover everything that can be visited in the Museo Campano di Capua!

The Roman bridge

The main street of Capua follows the route of the Roman consular Appia. The north-west segment (to the right of the Town Hall) leads to the Volturno, crossed by a bridge still known as Ponte Romano despite the fact that it is a modern reconstruction of the ancient structure, destroyed by bombing in 1943.

The Port of Capua

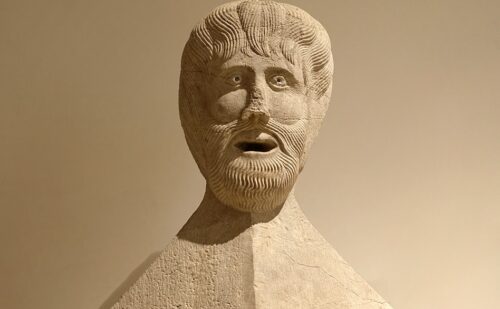

At the end of the Roman Bridge there are the Towers of Frederick II, or what remains of the famous Capua gate, which in the past aroused the admiration of poets and architects (Francesco di Giorgio Martini outlined a sketch). The Swabian emperor was not the simple client of the structure, but took an active part in the project, suggesting the political-ideological subjects of the sculptural decoration and the content of the epigraphs that adorned the door, which, in the intentions of the sovereign, should not represent only the access point to the city, but a real monumental entrance to the kingdom of Sicily. Begun in 1233 and completed in 1239-40, the gate was demolished in 1557 as part of the renovation of the walls commissioned by the Spaniards. The bases of the two towers that stood on the sides remain of the structure, while the sculptures that adorned it are kept in the Campano Museum.

The Cathedral of Capua

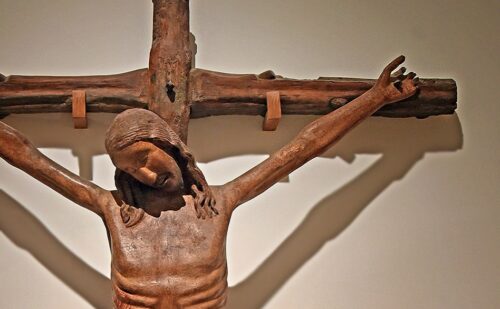

The bombing of 9 September 1943 damaged the building, almost completely erasing the traces of its historical stratification. Built in 856 and dedicated to Saints Stephen and Agata, the church was in fact rebuilt several times until 1850; after the Second World War it was rebuilt in its present form and then rededicated in 1957. On the right side is the bell tower (IX-XI century), with three planes of mullioned windows and with ancient Corinthian columns in the base, in which various bas-reliefs have been embedded coming from the Campanian Amphitheater. The interior is divided into three naves separated by 18 granite columns; the first arch of the right aisle leads to an entrance to the Bishop’s Palace, near which there is a marble portal originating from the destroyed church of S. Giovanni delle Monache. Among the works kept in the Cathedral, the candlestick of the paschal candle, from the 13th century, and, in the apse, an Assumption by Francesco Sole- mena; in the crypt (18th century) there is a chapel with a marble dead Christ by Matteo Bottiglieri (1724).

The Diocesan Museum

Next to the Cathedral, in the complex that includes the Bishop’s Palace and the seminary, is the Diocesan Museum, which collects works from the various city churches. Along the tour, illustrated by explanatory panels, you can admire sacred vestments and liturgical ornaments dating from the 11th century onwards (including the cope of Cardinal Bellarmine), and a series of architectural elements from the Lombard period. Among the altar frontals, the one depicting St. Martin on horseback in the act of dividing his cloak (17th century) is noteworthy. Only with the authorization of the archbishop can you ask to visit the precious Treasury of the Cathedral, rich in documents, objects from the Lombard period to the 20th century. The collection of parchments, dating back to the Lombards and recently restored, is remarkable and unique; it includes an ‘Exultet’ which took place in scrolls from the pulpit and which reproduces the central part of the Easter functions in miniatures, and the Evangelary of the Bishop Alfano, a very precious and unique work, made in Norman times by the Palermo goldsmiths of the Sicilian court.

The castles of Capua

The importance of the second of the castles of Capua grew in the eighteenth century, when the King of the Two Sicilies Charles of Bourbon placed Capua at the center of an imposing military system in Terra di Lavoro.

Castle of King Charles V

The Castle of Charles V is an extraordinary jewel of military architecture. Built between 1522 and 1543, the Castle of Charles V has a square shape with the unmistakable massive and sharp corner bastions, creating a four-leaf clover shape.

The Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, in 1536 wanted it to defend the strategic Via Appia and the two entrance gates of the city, Porta Napoli and Porta Roma, kept under control thanks to the cannons aimed at the ramparts of the walls.

In the nineteenth century the function of the structure was converted, at the behest of the Bourbon house, into a prison for the revolutionary protagonists of the uprisings of 1848. Subsequently, with the Savoy, it returned to its military function by hosting the Laboratories of the Army’s Pyrotechnic Office.

Lombard churches

Of early medieval origin, this area includes a large number of churches of Lombard foundation. “S. Giovanni a Corte” and “S. Michele a Corte” retain fragments of frescoes; “S. Salvatore a Corte” from the 10th century, boasts a small two-storey bell tower with mullioned windows, three arches on the facade already facing the portico and, inside, columns with Lombard capitals and traces of frescoes. The Diocesan Museum of Modern Sacred Art has been set up in the church, which gathers a remarkable collection of works – especially paintings – in a highly suggestive environment.

The three chapels perhaps carried out, in addition to the religious functions, the task of supervising the access points to the Corte area; in fact, in Longobard society, even the religious generally had obligations of civic supervision.

The church of Ss. Rufo e Carponio has a 13th century bell tower. S. Marcello Maggiore, founded in the twelfth century but rebuilt in the nineteenth century, retains a side portal composed of elements of disparate provenance: the architrave is a sepulchral inscription of the first count of Capua Audoalt the uprights are among the most interesting Romanesque sculptures of the Campania.

Porta Napoli, ramparts and defensive walls

On the southern edge of the walled city, in the square of the same name, is the monumental entrance to the city for those coming from Naples, created at the end of the 16th century. Crossing it, you can see the richly decorated external arch.

The ancient walls were rebuilt or strengthened several times over the centuries, but today’s appearance characterized by polygonal bastions and inclined curtains, constitutes one of the most important Italian examples of 16th century fortification.

From the bridge you can enjoy a beautiful view of the sixteenth-century area of the city.

Church of the Annunciation

Along the stretch of Corso Appio heading south-east (to the left of the Town Hall) stands the church of the Annunziata, founded at the end of the 13th century but rebuilt between 1531 and 1574 and completed in the Baroque period; it is dominated by a dome designed by Domenico Fontana. The church was severely damaged by an air raid on 9 September 1943. On the high and narrow facade, characterized by a remarkable portal, there are the statues of Sant’Antonio Abate and Santa Lucia, placed in niches. The interior, with a Latin cross nave, houses some eighteenth-century paintings and a carved and inlaid wooden choir from the Benedictine convent of Capua, built in 1519 and depicting scenes from the life of Christ.

The Royal Hall of Arms

At the end of Via dei Principi Normanni you will find the octagonal structure that houses the Royal Weapons Hall, originally a Baroque church annexed to the convent of San Giovanni delle Monache. Inside there is an impressive wooden structure with independent stairs, created to store firearms in a series of racks.

It was the Napoleonic military who transformed it into a military structure and, when the Bourbons returned to the city in 1815, it was decided to keep its new function.

Square of the Judges

Here stands the Governor’s palace (1561 today the town hall), which bears seven keystones on the facade, in the form of busts of divinities, from the Amphitheater of Santa Maria Capua Vetere. On the right stands the bust of San Eligio, rebuilt in the Baroque period (1747), flanked by the fifteenth-century arch of the same name (XIII century), with cross vaults and a loggia above. Overlooking the square is the seventeenth-century Palazzo della Gran Guardia or Bivach, restored several times, surmounted by a statue of King Charles II (1676).

Passing under the arch of S. Eligio along via Alessio Mazzocchi, where the remains of the unfinished bell tower of S Eligio are found, and ends on the Via Appia in front of the Castle commissioned by Charles V and built in 1542 on a project by Gian Giacomo dell’Acaya. Despite the extensive damage caused by the bombings of the last world war, the building retains much of its majestic original appearance and is one of the main monuments of the city; it can be visited on request.

External link