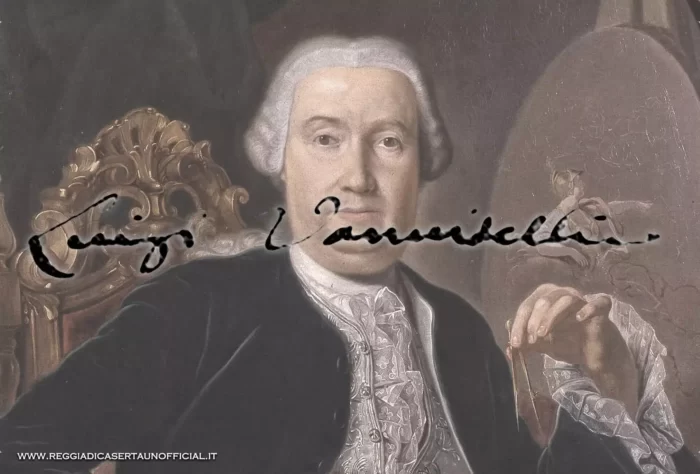

Luigi Vanvitelli, the Architect of the Royal Palace of Caserta

Luigi Vanvitelli was a revolutionary genius with a tireless and concrete mind, and father of the neoclassical architecture. He was admired by everyone, and envied by many.

Luigi Vanvitelli (Naples, 1700 – Caserta, 1773) was an architect, engineer, scenographer and italian painter. Born from by famous landscape artist Gaspar van Wittel, he soon became popular due to his outstanding artistic talents, so as to immediately receive the praises by Filippo Juvarra, one of the main baroque architects.

He deeply renewed the architecture, he had many students, imitators and followers, so many that in time his style spread so much in Italy and Europe, to create a new style: the neoclassical architecture.

He created and restored many buildings throughout Italy. His remarkable abilities made him become the main architect of the Pope, but this attracted jealousies and dislikes. In Rome, among many works, there was also the securing of the dome of St. Peter.

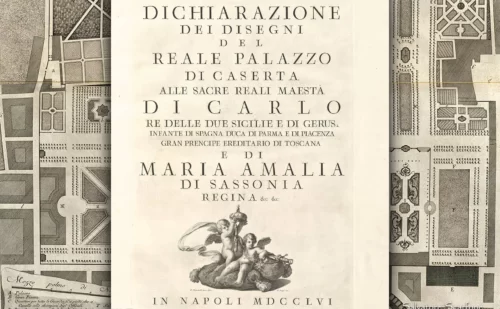

The new king of Naples, Charles of Bourbon , to create the new nerve centre of his reign, asked to Vanvitelli to design the new city of Caserta, including the Royal Palace as its centerpiece. Its project, immediately printed and distributed across Europe, obtained great admiration by the sovereigns, and this admiration atttracted to him dislikes and even bullying.

After his death in 1773, the works of the Royal Palace were keeped on by his son Carlo.

INDEX

- Introduction

- The origins

- The thought

- The first works

- The return to Rome

- From Rome to Naples

- Some works

- The Royal Palace of Caserta

- Examples of works inspired by the Royal Palace of Caserta

- Pupils and followers of the time

- Prestige and mobbing at the court

- The last works

- Other works

- The last project and death

- The family

The origins of Vanvitelli

Luigi Vanvitelli, (Napoli, 1700 – Caserta, 1773) a personality that is difficult to be limited within a specific style or artistic current, as it is no more fully Baroque, but at the same time a forerunner of the following style, the Neoclassical one.

So he was a transitional figure, in an era of profound social changes and thought, living the transition from the absolute monarchy, to the enlightened one. Vanvitelli fully reflect these contradictions, summarizing and integrating them into his personality.

Luigi Vanvitelli was born on 12 May 1700 in Naples, where his father, the famous landscape painter Gaspar Van Wittel, was called by the Viceroy of Naples Luis Francisco de la Cerda y Aragón, Duke of Medinaceli, to decorate the rooms of the Royal Palace. It was in honor of the viceroy that the father was ordered to give his son the name of Luigi (the Italianized version of Luis).

He grew up in Rome under the guidance of his maternal grandfather, Andrea Lorenzani – an artist himself – and his father, who sometimes passed him his sketchbooks, encouraging him to continue. Luigi was educated in the taste of classicism through direct observation of the many great ancient and modern Roman monuments.

(Gaspar van Wittel era il padre di Vanvitelli, il cui cognome originario fu italianizzato)

The beginning of the career

In 1715, Filippo Juvarra, one of the main Baroque architects, was in Rome to design a new sacristy for the Vatican Basilica, he was able to examine Luigi’s drawings and, as Lyon Pascoli tells:

“… He praised them very much, and showed astonishment, that at a young age he worked like a skilled man. He urged him to persevere in his studies, telling them what a better fortune he would have made in these, than in those of painting, because there were many painters who then practiced art with fame, and architects were rare. “

This strongly spurred the artistic vein of Luigi Vanvitelli, who considered Juvarra a Master, and it was thus that he became a close collaborator and assistant of his father, from whose paintings he learned that typical style made up of large spaces full of light evident in his architectures. On the other hand, in the views of Gaspar Van Wittel, the architectural and urban elements prevail over the figures, almost as if the architecture itself became a natural landscape. The “real landscape”, as opposed to the “ideal landscape”, is Gaspar va Wittel’s deepest and most valid teaching.

After his first steps as a scenographer and as a painter, in 1726 he became assistant architect of G. Antonio Valerio in S. Pietro and acquired ever greater prestige in the Roman cultural environment, so much so that in 1728 he was welcomed into the Academy of Arcadia, a literary academy born to counter the so-called “bad taste” of the Baroque, through the return to more classical forms.

As for the architectural events, however, we cannot ignore the influences that Luigi Vanvitelli matured from the architects of previous generations, not only Italians. Among the various influences we mainly remember, in addition to the aforementioned Filippo Juvarra, also the main architects operating in Austria, Germany, Spain, the team that began the works of Versailles, composed of Louis Le Vau, André Le Notre and Charles Le Brun, as well as the protagonists of baroque classicism. The activity of Luigi Vanvitelli presupposes the activity of the first generation of Baroque architects: Pietro da Cortona, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Francesco Borromini and the younger Guarino Guarini. In reality, the historical depth of Vanvitell’s work is more extensive (it has its roots in the seventeenth century) than that of the political and cultural events, starting with the early XVIII century.

The thought of Vanvitelli

Luigi Vanvitelli was not indifferent to the Neapolitan Enlightenment orientation and the other European capitals. Among the main characters of this cultural movement we mention:

- the call to activism and productivity,

- the “reductive” and popular nature of cultural acquisitions matured abroad,

- the problem of language in the field of teaching and scientific research;

- the birth of a more modern urban planning concept,

- the function of aristocratic salons,

- the new role of women in society

- the discovery of Herculaneum and Pompeii

etc.

The theme of the rediscovery of Herculaneum and Pompeii never appears in Luigi Vanvitelli’s letters to his brother Urbano. Most likely he had no interest in archeology and antiques.

As a practical man he was, Vanvitelli hated the most conceptual and erudite theories, just as he had a notable aversion to architectural theory and criticism:

“Do not trust the advice of men of good talent in difficult things, but rather of mature and rested men; because the beautiful talents are mostly restless, so they cannot have sound advice like the year when modest and serious men. Know that great things, and especially States, are governed more with reputation and with vigilance that nothing is done, if not very well thought out, than by other means. But the vivacity of the beautiful genius wont produce all contrary effects, and often upset the good ones, because it is restless in itself. And keep it certain that where there is no firmness it cannot be prudence ”.

He almost certainly believed that the architectural code was something definitively acquired and so elastic as to incorporate the baroque exceptions:

“From the Renaissance onwards, the history of architecture had developed seamlessly, so the militant architect was only allowed to use this code, use its terms to express works-messages.”

His opinion about Versailles

Versailles, as is well known, was the touchstone of all the royal palaces in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. On Versailles we know the opinion that Vanvitelli expressed in 1760, when he examines a volume with the architectural projects of the entire complex of works commissioned by Louis XIV: a summary and absolutely negative judgment:

“I have tried to have a book in sheet, where the factories of the Louvre and the Tuiglerie of Paris are expressed, Bernini’s thought for the Louvre, which was not put in place, the Palace of Versailles in all its parts. Oh God, what is this! It costs me 23 ducats, so expensive they sell it; on the other hand it gave me consolation: in Versaglies there is nothing, and in the rest there is little; … “

Despite this opinion expressed, however, Vanvitelli constantly compares his work with the French one, as the following passage about the chapel demonstrates:

“My Chapel in Caserta, he argues, will be the best piece and that of Versaglies is so bad, disproportionate in everything, although full of gilded bronzes, which is absolutely a bad thing, but it is not the Chapel of Versaglies that I suspect to make the loggia around; it was the order of the King, who wanted the Court to be fully under his eye when it was courting and kissing hands. Landes say these Lords badly; more, everything is reduced in a good symmetry of architecture and comfortable, and they try to find out if these comforts are elsewhere ”.

The first works

Rome

The Vanvitelli’s project for the Trevi Fountain

The good tests offered on this occasion led to the nomination as architect of the Reverend Apostolic Chamber and the commission to build the Vermicino aqueduct in a fraction of Rome, which he completed in 1731. His friend had been a collaborator in the work. brother Nicola Salvi, who was his luckiest competitor in the competition for the Trevi fountain. In fact, during these years two competitions were launched: one for the facade of S. Giovanni in Laterano, the other for the Trevi fountain. Vanvitelli participated in both, but the first was won by Galilei, the second, Nicola Salvi.

Ancona

Lazzaretto – Ancona

His projects, however, impressed the examiners so much that he was entrusted with the works to be carried out in Ancona: the Lazzaretto and the Port. The project of the Lazzaretto dates back to 1734. The works began immediately but went on for a long time due to various difficulties, especially of a local political nature.

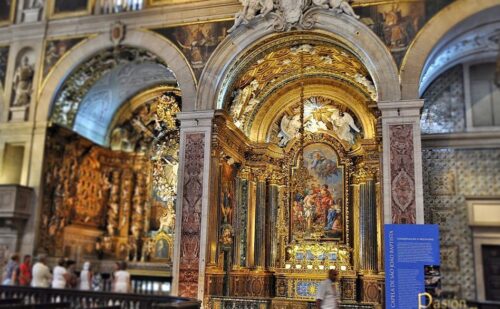

After much controversy, the works in Ancona were suspended in 1740 to be resumed only in 1754, at the end of the pontificate of Benedict XIV, but entrusted to Carlo Marchionni. Luigi Vanvitelli was very embittered at not having been called to complete the work, which, however, was completed according to his designs. Meanwhile, in Ancona he had also completed other works: the Chapel of the Relics in the Cathedral of S. Ciriaco in 1739; the church of Gesù in 1743, where the shell appears for the first time as a decorative element, which later became typical of his style; the church of S. Agostino, now transformed into a dormitory for the Navy, the Bourbon del Monte Palace, now Jona, and other factories of which we have lost news.

The return to Rome

Luigi Vanvitelli was considered by the Church worthy of succeeding the genius of Michelangelo and, therefore, in 1742 he was called to solve the static problems that had arisen in the dome of St. Peter, the universal symbol of Christianity and even the first icon – together with the Colosseum, the Triumphal Arches , the obelisks and the dome of the Pantheon – of Rome Caput Mundi. The dome, almost since its completion, always gave serious concerns, and in 1742 it was considered in danger of collapse. From “Architect of the Reverenda Fabbrica” of San Pietro, after careful surveys and analyzes, Luigi Vanvitelli presented, on September 20, 1742, a report in which he denounced the seriousness of the damage and proposed the iron ring of the dome, damage also confirmed by a commission of three mathematicians appointed by the pope. Having chosen Vanvitelli’s proposal sparked a violent controversy among the various figures appointed by the papal court, including Fuga. The Pope, after appointing three other commissions, decided to ask for the arbitration of Giovanni Poleni, a famous Paduan mathematician and architect, who preferred the proposals of Vanvitelli, praising above all the originality of the method for tightening the circles. So, finally, the work was entrusted to him but the success of the enterprise was embittered by the harsh criticism of Fuga and Monsignor Giovanni Gaetano Bottari, who even published an anonymous dossier against him. Full of praise, however, it was always Poleni who openly praised his works, including the project for the facade of the Milan Cathedral, drawn up in 1745 at the request of Giorgio Pio Pallavicini.

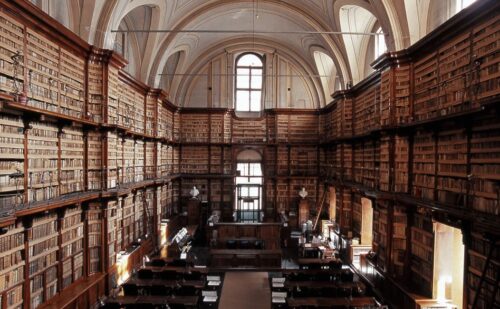

The Royal Chapel of Lisbon in Portugal

In the same years he was commissioned to design the Royal Chapel of St. John the Baptist in the church of St. Rocco in Lisbon, initially intended for Salvi, but the latter, also due to health problems, had asked for Vanvitelli’s intervention. While the works for the Lisbon chapel were still in progress, in 1746, Vanvitelli set his hand on the construction of the convent of S. Agostino, in Rome. The works lasted for over 10 years, so he, working in Caserta, had to entrust the execution first to Rinaldi and then to Murena. In 1748 he was entrusted with the restoration of another Michelangelo church: S. Maria degli Angeli, built on the ruins of the Baths of Diocletian. Despite every precaution, this work too was harshly criticized above all by that Monsignor Bottari, an irreducible opponent of Vanvitelli and an advocate of Fuga, a fellow countryman of him. Among the other numerous works of these years we remember at least the arrangement of the ports of Anzio and Fiumicino, also accompanied by a train of controversy.

From Rome to Naples

In 1751 he moved to Naples, in the service of the young and ambitious King Charles III of Bourbon, who had commissioned him to build the Royal Palace of Caserta. See History of the Palace

As a tireless artist, while he was building the Palace, he was simultaneously busy with important public works for the Pope, and at the same time he performed other works for the Roman and Neapolitan nobility. When the Habsburgs, the Austrian royal family, also proposed the renovation of the royal palace in Milan, Vanvitelli had to entrust it to an architect from his circle, Giuseppe Piermarini from Foligno.

A huge activity, with nothing left to chance, improvised or neglected. In Vanvitelli’s mind every problem always finds a double solution: artistic and practical. His rule was “the union of beauty and utility”. The Carolino aqueduct can be cited as a typical example: after having given life to the waterfalls and fountains of the park, the water would have been channeled towards Naples for the needs of the city.

Vanvitelli did not always have positive relations with Neapolitan artists. He had a purely classical stylistic conception, therefore he refused in any way to collaborate with artists such as, for example, Giuseppe Bonito, director of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, and others like him still very attached to the Baroque style. Instead he appreciated other artists such as, for example, Sebastiano Conca. In any case, both were involved in the decoration of the Palatine Chapel.

Some works

The Royal Palace of Caserta

In 1750 the King of Naples, Charles of Bourbon took Vanvitelli in the design of a new royal palace that was designed for the city of Caserta , easily accessible from the capital , but differs from it, as it was Versailles from Paris . The palace, which was to be built near a new city (which was later made in later times, in a chaotic way, without taking into account the ideas of Vanvitelli), was supplied with water from the monumental Carolino Aqueduct , designed by Vanvitelli on the model of hydraulic works of ancient Rome .

The Royal Palace of Caserta, defined as the last great creation of the Italian Baroque, is certainly his most important work. With great attention to detail and spread over four monumental courtyards, the building is faced by a spectacular park that exploits the natural slope of the land to articulate itself in a giant artificial waterfall, punctuated by a series of fountains and marble statues. Some of the most spectacular parts are undoubtedly the monumental staircase, the chapel and the court theater. Without the four corner towers and the central dome, which should have moved its bulk, the palace became a source of inspiration for all subsequent architects.

After his death, the works on the palace were continued by his son Carlo (Naples, 1739 – 1821).

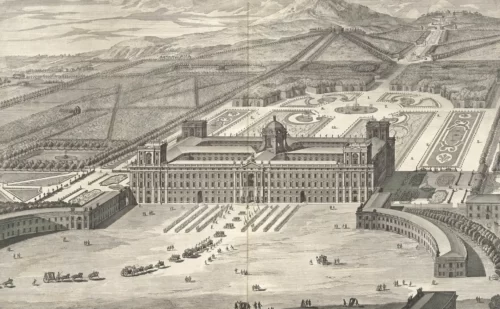

The bird’s-eye view by Vanvitelli, with the first design of the Palace. Note the never built Parterre due to lack of funds

Examples of works inspired by the Royal Palace of Caserta

Observing all architectures built or modified after the publication of the Declaration of Drawings of the Royal Palace of Caserta, you can often recognize its influence. For example, the Staircase of Honour of the Royal Palace, was taken as a model for the construction of the world’s most beautiful staircases. It is easy to find its style (central staircase thta splits into two lateral staircases ending in a large tripartite wall) also via a simple image search via web.

The inspiration was often taken from the initial project which was printed and spread throughout Europe, but which was modified at a later time.

Pupils and followers of Vanvitelli of the time

These were the main pupils and followers of Luigi Vanvitelli, who drew inspiration from his teaching. Those who were inspired by them and by Vanvitelli, increasing over time came get to a new architectural standard: the Neoclassical.

In Italy

- Francesco e Arcangelo Vici,

- Pier Francesco Palmucci,

- Girolamo Mezzalancia

- Paolo Soratini

- Carlo Orazio Leopardi

- Francesco Matelicani

- Carlo Marchionni

- Francesco Maria Ciaraffoni

- Antonio Rinaldi

- Lorenzo Daretti

- Virginio Bracci

- Giovanni Andrea Lazzarini

- Tommaso Bicciagli

- Andrea Vici

- Giuseppe Tranquilli

- Mattia Capponi

- Giuseppe Lucatelli

- Gaetano Sintes

- Carlo Murena, discepolo prediletto

- Domenico Giovannini

- Virginio Bracci

- Andrea Vici

- Ermenegildo Sintes

- Pietro Bernasconi (master builder of the Palace)

- Francesco Sabatini

- Marcello Fonton

- Filippo Retrosi (continuer of Giovannini at Caserta)

- Francesco Collecini (the most gifted student of Vanvitelli)

- Giovan Battista Vaccarini

- Giuseppe Piermarini

- Antonio De Simone

- Carlo Vanvitelli (eldest son of Louis)

- Martin Biancourt (head gardener of the park)

- Antonio Rosz (carpenter and cabinetmaker)

- Carlo, Giovanbattista and Crispino Patturelli

- Domenico Brunelli, Giovan Battista Fontana and Leonardo Pinto

- Pietro Vanvitelli and Francesco Vanvitelli (children)

- Giovanni Patturelli

- Nicola Tagliacozzi

- Bartolomeo Vecchione

- Luca Vecchione

- Gennaro Papa

- Giuseppe Astarita

- Gaetano Barba

- Carlo Galli da Bibiena

- Carlo Vanvitelli

- Pompeo Schiantarelli

- Ignazio Di Nardo

- Giovanbattista Broggia

- Francesco Sicuro

- Vincenzo Ruffo

- Gioacchino Avellino

- Giovan Battista Vaccarini

- Stefano Ittar

- Venanzio Marvuglia

- Saverio Ricciulli

- Pompeo Schiantarelli

- Ignazio De Juliis

- Antonio Magri

- Vincenzo Ruffo

- Giuseppe Astarita

- Gaetano Barba

- Carlo Murena

- Giovan Pietro Cremoni

- Pietro Bernasconi

- Antonio Stefanucci

- Pietro Carlo Borboni

- Giuseppe Antonio Landi

- Cosimo Morelli

- Camillo Morigia

- Giuseppe Pistocchi

- Giuseppe Piermarini

- Simone Cantoni

In Spain

- Marcello Fonton

- Francesco Sabatini

- Pietro e Francesco Vanvitelli

In Belgium

- Laurent Benoit Dewez

In Russia

- Antonio Rinaldi

Prestige and mobbing at the court

During the first phase of the Neapolitan period, Vanvitelli was undoubtedly among the central characters of court life, enjoying the total esteem of the sovereigns, in particular of Queen Maria Amalia.

The architect enjoyed the protection of Fogliani, the most influential minister of the period; he informed himself about international politics by maintaining confidential relations with the foreign ambassadors who frequented the Neapolitan court, as well as making friends with all important figures and participating in all the various events.

The most illustrious personalities of the time passed through the Neapolitan house of Luigi Vanvitelli such as important politicians, nobles, prelates, artists, from Fogliani to Father Boscovich, from Abbot Galiani to Winckelmann …

Despite this success on a professional and public level, Vanvitelli in letters to his brother Don Urbano, monsignor in Rome, manifests frequent concerns and dissatisfactions, both for relations with Ferdinando Fuga (who was always his rival) and for the economic treatment, which he considered inadequate. to the activity carried out, and he hoped that the esteem that the sovereigns had for him, that this would guarantee him a safe future.

Meanwhile, the first conflicts and obstructions were already beginning at the Court: one day he was forced to make a plea to Tanucci, to obtain the charcoal for the brazier to heat his office in Caserta, charcoal, among other things, already distributed to the other offices:

Caserta 14 September 1756

Your Excellency Having Mr. and Knight Intendant Neroni made representation to V. E. who, as winter approached, lacked the necessary fire for accountancy, the Secretariat and my office where my young people are constantly employed in the Royal Service; and having in sequela SRM for his graceful clemency, who gave the charcoal during the winter to the workshops of this Intendenza, there was no person who explained the dispatch, who not being in the one expressly named, must remain excluded, as if this study, is not one of the Workshops of the Intendency: so when, as I suppose, it must remain included, depending on the representation of Mr. and Knight and Int. Neroni, and the need for the Season, I beg your , that the charcoal granted to me was given to me like the others, while with all respectful respect I am by V. Excellency

Humble most devout Obligatory most Servant

Luigi Vanvitelli

In 1759, Ferdinand VI of Spain died in the midst of the works on the Palace. Charles of Bourbon had to leave Naples to succeed his brother on the Spanish throne. He barely had time to see the Bridges of the Valley finished. With this departure, the dream of the new capital also vanished: that city that Maria Amalia had wished to be built “with good direction” and that Vanvitelli had already sketched in outline in the general project. “‘O rre piccirillo”, as Vanvitelli himself puts it, speaking of Ferdinand IV, he could not, for his age, make decisions. Everything was now in the hands of Tanucci, who presided over the Regency Council of the Kingdom and who had a considerable aversion to Vanvitelli. Everything became more difficult for ours. The humiliations are countless. Tanucci found every pretext to reduce expenses, thus delaying construction. Intendant Neroni came to suggest that he seek advice from military engineers in some difficult cases. Vanvitelli, resentful, recalling the bad test given by them, promptly replied:

“On the other hand V.E. reflect, that if I had had to ask advice to build the Royal Palace, and the difficult conduction of the waters, I would never have (sic!) built the Palace, nor these conduits and consequently, I would not have been able to serve the King in anything. The essay is enough that the most accredited and accept experts and mathematicians, after the departure of S.M.C. they had no difficulty in ensuring the Court and the Minister that it was impossible that the water would reach the aqueduct in Caserta. Or what opinion could I ever draw from these? ».

Except for the friendship of Abbot Galiani, Vanvitelli could not count on anyone else, because everyone wanted to be on the side of the powerful Tanucci, who preferred Fuga, a Tuscan like him. Some works were stolen from him. Even the most trusted master builder Bernasconi dared to appropriate his project for the parish church of Caserta. Called to Benevento for the bridge over the Calore, not only was he not paid, but he was asked to rent the buggy used for the inspection!

The last works

The worldly life did not attract him, but, when his work commitments allowed him, he went to the theater, especially at the San Carlo, and played the lottery. The inconveniences at court, and the ailments of age, pushed him to stay longer and longer in Caserta. His home was adjacent to the church of S. Elena, so much so that he asked and obtained authorization to make an opening in the wall, so that he could attend religious services while remaining at home.

Despite his age, Luigi was always busy with multiple commitments. In 1769 he had gone back to Milan, in the company of Piermarini, at the invitation of the Count of Firmian, to restore the Ducal Palace. His project included an extensive renovation of the facade, harmonizing it with the nearby cathedral and the arrangement of the entire surrounding area. The court of Vienna, however, found it excessive and he, having left the post to Piermarini, returned to Naples. Meanwhile, during his stay in Milan, he had also drawn up the project for the Loggia of Brescia, which, modified in 1771, will only be approved in May 1773, after his death.

Other works

Biographers remembers the works made in Macerata for Gualtiero Marefoschi; in Pesaro, where he left the construction management to his disciple Antonio Rinaldi, who after became famous at the russian court of the Tsars; in Loreto, where he completed the loggia of the Apostolic Palace, made by Bramante, and added to the monumental bell tower. Maybe he only designed the St. Vitus Church in Recanati, the Franciscan Convent in Fano, and more. While working in Ancona, in 1739 Luigi Vanvitelli was called to Perugia to build the church and convent of the Olivetan. The project, of which there are some drawings in Caserta, was later made by Murena in 1762. The restoration of the Romanesque cathedral of Foligno is the last work in Umbria. Still in Siena, however, it documents the activities for the project of the St. Augustine Church. The many commitments in the Marches, Umbria and Tuscany, however, didn’t reduced his works and relations in Rome, where he was the main architect of St. Peter’s. After the aqueduct of Vermicino, the most important work of which he was in charge was, in 1741, the restoration of the Jesuit Villa Tuscolana in Frascati, also called “Rufinella” from the name of Rufino Cardinal who had owned. Two years later in Civitavecchia he erected the foutain at the harbor.

The last project and death

In 1767 he was commissioned to prepare the apparatuses for Ferdinand IV’s wedding with Maria Giuseppa, and, after her sudden death, with Maria Carolina, celebrated in 1768. The King wanted the Court Theater of Caserta to be ready, but did not make it in time. The party was celebrated in Palazzo Teora at the marina (now Riviera) of Chiaja where another ballroom was set up on the garden side. Also for the baptism of the Infanta royal, Maria Teresa Carolina, whose celebrations took place in Palazzo Perrelli on 6 September 1772, Vanvitelli set up an elliptical ballroom in the garden. In some niches he placed the portraits of Charles III, Ferdinand IV, Maria Carolina and the Infanta. The vault depicted the symbolism of the dominion of the four branches of the Bourbon family, of the peace and prosperity that they would bring to humanity. In addition to the ballroom, a temporary theater was also set up for the representation of the “Cerere placata” by the musician Niccolò Jommelli from Aversa.

As he had begun, therefore, as a painter and set designer, Luigi Vanvitelli concluded his intense work as an artist. By now tired, disappointed, embittered, he retired definitively to Caserta where he died on 1 March 1773. Almost forgotten, without even a plaque, he was buried in S. Francesco di Paola, the small church next to his superb palace.

The family of Vanvitelli

While working in Ancona, Vanvitelli often returned to Rome worried about his father’s health, who had already completely lost one eye in an attempt to remove a cataract. On September 13, 1736, at the age of eighty-three, Gaspar died. Three months later, on December 16, his wife followed him to the grave. The following year, in 1737, Luigi married Olimpia Starich, daughter of an accountant from the S. Pietro factory. From their marriage were born:

- Carlo in 1739. He became an architect, and continued the works of the Royal Palace after the death of his father;

- Pietro in 1741; Francesco in 1745. They became military architects, and followed King Charles of Bourbon, when he moved to Spain to become King in place of his half-brother Ferdinand VI who died in 1759.

- Gaspar in 1743. He became a magistrate in Naples;

- Thomas in 1744; died one month old;

- Anna Maria in 1747, who died at the age of 5;

- Maria Cecilia in 1748. In 1764 she married the architect Francesco Sabatini, a pupil of her father;

- Maria Palmira in 1750. In 1767 she married Giacomo Vetromile, a lawyer and Knight of the Constantinian Order.